If you read my post Under African Skies [August 4th 2024], you’ll know I attended the very happy 99th birthday party for a former District Commissioner in East Africa. Following a week of dog and house sitting in the Sussex countryside blessed by beautiful weather, my contemplation of the local environment, as in my last post Once in a Blue Moon [21st August 2024] merged with my admiration for the man himself. The result, this draft, let’s call it a photo-poem, celebrating the District Commissioner and the district where he now lives. Let’s call it Edgerley.

Edgerley

The light reaches into, along, through, the evening English oak, sunlit bark of heavy-leafed boughs, risen above hedgerows, August foliage as if electro-formed, or poured from molten.

The shy horses' furtive approach and slow swerve away, the hefty head dipped to munch the child's wrenched handful of grass tossed to hoof. Crows, jackdaws, and rooks scatter above the wood pigeons flapping from the stubble, grey tummies bloated by the remnant wheat.

A small deer cruises through the evening light, legs like stilts. It’s all alone, gone before a buzzard settles on a post to watch the summer field, spook the pigeons once again, which burst like clays in all directions from their business in the stubble hunting grain.

The buzzard sways, steadying, plumage an upward fan until its yellow feet and talons clench its place, secure, on its sturdy, tendoned legs, dark grey and shaggy at the hips, tail of black and tan a kind of keel; head, breast and shoulders mottled with feathers the colours of dark earth and chalk. It spreads its wings as if to gauge the air or wind, then turns its beak-hook and its eye to profile, then full face. A white spot like another eye glares from the centre of its horny upper beak.

In the the head's curve, in the feathery escarpment of its owl-

like cheeks, in the intensity of its focus on all that is, there’s

a gentleness, a playfulness, a raptor’s rapport with its prey,

unknowing human harm, regret or guilt. It wheels from its

perch, to reveal below each great swoop of wing, its roundels

like a warplane's insignia.

Nearby on power lines along

another field's edge, rare summer visitors bounce gently on

the wire, and seem to smile together an ironic smile, knowing

– these Ortolan buntings – they've escaped the over-feeding

in the dark, the drowning in Armagnac, the secret ritual of

eating their golden, scorched remains beneath a towel

to enhance aroma or hide the guilty glutton from the gaze

of those who believe the little creatures must be protected,

come what may; and come what may, may be the buzzard,

hard on their heels as they fly off towards the west. Yet again

the pigeons return to pursue their waddling among the stalks

of gold, and from that little window in the house, an old man

observes the activities of the eventful day and busier night.At first there was a summoning, the eastern horizon giving birth to a giant orange orb floating above the trees, rising like a sun, but this is the cold moon, a super moon, orbiting closer to the earth than usual, so bigger and brighter, although smoke particles from forest fires an ocean away, swept by the jet stream, act as a photographic filter in the upper atmosphere – to turn the moon the colour of flame. But it’s a blue moon too – this man, toad, woman, hare – a blue super moon. Later it will lose its fiery majesty to resume its icy stare, stark in the stars in their black firmament, or cloud-softened and rainbow-edged by the weather front’s massive blanket of nimbostratus, sliding inexorably north east.

Beneath the hidden moon, the flowers and plants keep vigil through the night, awakening to their work of photosynthesis giving oxygen to light: the creeping thistle with seed heads a weft of spangled stars;

the butter-wrapping bitter dock, soother of nettle stings; chamomile, bristly oxtongue; bird vetch; wood cranesbill which gave a blue-grey dye, known as Odin’s Grace, to colour the cloaks of warriors and protect them in battle;

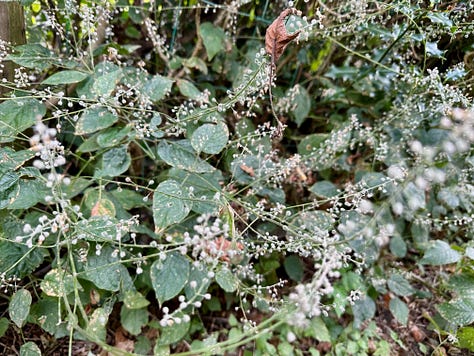

Lady’s thumb that gets its name from the black marks on its leaves; the delicate tracery of enchanter’s-nightshade, the witch-flower; the field bindweed, creeping Jenny, known as Our Lady’s Little Glass, according to the Hanau brothers’ fairy tale of the wagon loaded with wine stuck fast in mud. Our Lady, the Virgin Mary, passing by, offered her help in return for a glass of wine. The waggoner agreed but had no glass, so Mary plucked a field bindweed flower which he filled, and once she’ d sipped the wagon was set free and the waggoner drove on.

Nestled in the hedgerow undergrowth is cuckoo pint that has a dozen other names, many with sexual overtones and mostly now unused: dog’s cocks, willy lily, naked boys, naked girls, priest’s pintle (a pintle being a penis), Adam and Eve, soldiers diddies, friar’s cowl, snakeshead, and still commonly used, Lords and Ladies. The thick fleshy rod that rises through a sheathing spathe is simply a strange attractor for pollen hunters. The flowers themselves are unisexual unlike most English flora which are hermaphroditic. The male flower sits above the female, below the risen spathe, below a ring of hairs to forestall smaller flies and facilitate the transfer of pollen from the male anther to the stigmas of the female. By the autumn, the protruding spathe dies away. The female flowers fruit in a little tower of clustered crimson berries.

Bees are the catalytic aviators in all this change. Their compound eyes are made up of many tiny lenses or ommatidia, each attached to an optic nerve to create high-definition images of the bee’s environment. They see UV, and use this gift, together with their remarkable sense of smell, to find and navigate the flight paths into flowers following each plant’s unique and secret code of polarisation – patterns of dots or stripes or contrasting colours on the petals, patterns unseen by human eyes, that act as nectar guides for bees into every shape of flower, funnelform or craterform, coronate or galeate, campanulate, labiate, papilionaceous...

Navigating mainly by the Sun, but also by the polarisation pattern of the sky and by Earth’s magnetic field, in flight their wings can beat 230 times a second. Their sex determination system is haplodiploid. Females are often ‘suspersisters’, more closely related to their sisters than to their own offspring.

The flowers of large bindweed are irresistible to bees, as are those of ragwort, which produces the most nectar, and knapweed, the most nectar and pollen combined.

After producing its own nectar, the cow parsnip flowers

develop into a drone-like mobile sculpture, and once

dispersed, its circular array of seed pods becomes

a filigree of stars.

In English folklore, bees once were told

of important household news. So I stand now in the stubble

field to tell the unseen swarm huddled in your son’s new

hive about your ninety-ninth birthday party, and how I believe

as full of life as the world around you that you love,

you’ll reach a century and the unwanted letter from a king.