I’m pretty late with my post for last week which I’m blaming on my visits to Hickstead showjumping on Wednesday and the Imperial war Museum on Thursday (more research on remount horses), and a visit to Charleston farmhouse on Saturday. All very pleasant ways of not meeting a deadline.1

This is probably the beginning of a long ramble that could last several weeks, as I explore some of the intricate and (for me!) fascinating connections mis en abyme has fetched up.

But ‘bear with me’ as call centre staff constantly request me to do, on phone calls that involve negotiating with the great god Database.

The age of reflexivity

Given my predilection for reflexivity I think it’s interesting that I’m a child of the reflexive era. Here’s a chart of the frequency of usage of the word ‘reflexivity’ from the OED which rather matches my own lifespan so far, since 1950 anyway.

When I’m fascinated by a particular theme, topic, historical figure or object, I easily become sensitised to it. I find myself constantly, but mostly unconsciously, scanning for references, connections, representations in the field of my mental peripheral vision, constantly alert for significance, albeit a significance I’m creating reflexively, by the very act of my connective searching.

So it is, with my focus on mise en abyme.

There it is in Natalie Portman’s new ‘vehicle’ on Apple TV, Lady of the Lake.

There it is in The Hard Zone, Andrew Hagan’s article about the attempted assassination of Donald Trump (London Review of Books 1.8.24).

This fantasia, a fiction inside a fiction inside a reality, had the vital energy of seeming more plausible than the truth. And that is our world. Conspiracy nowadays may be as fleet as thought, and theories of fiction gather around every true event.

And there’s the abyme in Daniel Kehlmann’s article about AI in The Guardian

Not yet panicking about AI? You should be – there’s little time left to rein it in

OpenAI has to employ hundreds of poorly paid workers in the global south to forcibly suppress the natural tendency of the large language model to utter angry obscenities, insults and nastiness – the now well-known polite, calm tone of the chatbot requires a lot of filtering. Jacques Lacan was right; language is dark and obscene in its depths.

Supping with the devil

In a kind of mise en abyme experiment, I asked Chat GPT what it thought on the subject and it came back with what I reckon is a pretty coherent and convincing response. For me it passed the Turing Test with flying colours.

Chat GPT mise en abyme

It replied to my question:

Social media platforms epitomize the concept of mise en abîme, creating endless layers of self-reflection and self-promotion. Users curate their lives, presenting a carefully constructed narrative within the broader story of their actual existence. This phenomenon often leads to a recursive loop where individuals become trapped in their representations, blurring the lines between reality and illusion.

The pursuit of online validation can result in self-sabotage, akin to being "hoist on one's own petard." As individuals strive to present an idealized version of themselves, they may inadvertently expose vulnerabilities, suffer backlash, or face the consequences of their actions. The very tools designed to enhance self-promotion can turn against their users, creating a dramatic irony reminiscent of Shakespearean tragedy.

The existential threats faced by endangered species further illustrate the complexities of modern existence. The ongoing destruction of habitats and ecosystems is a stark reminder of humanity's self-destructive tendencies. In this narrative, humans are both the protagonists and antagonists, creating a tragic mise en abîme where efforts to progress and develop simultaneously undermine the very foundations of life on Earth.

The plight of endangered species serves as a metaphor for the broader ecological crisis, highlighting the interconnectedness of all life forms. This recursive narrative – where human actions endanger other species, which in turn threatens human survival – underscores the paradoxical nature of progress and the unintended consequences of our pursuit of advancement.

The dream of interplanetary colonization thus becomes another layer in the recursive narrative of human existence, reflecting both our ingenuity and our inability to address fundamental issues on Earth. This aspiration encapsulates the ultimate irony of being "hoist on one's own petard": in seeking to escape our problems, we may carry them with us to new worlds, perpetuating the cycle of self-destruction.

If you can’t beat them, intersect with them

Parallel realities

I’m alert to other live interests too, that often intersect with each other.

While on holiday we visited Il Vittoriale degli Italiani, at Gardone Riviera on the shores of Lake Garda. This extraordinary estate commemorates one man in particular, the poet-soldier Gabriele d’Annunzio, Italy’s hero of the First World War.

As I’m writing about Rowena Cade and The Minack Theatre on the cliffs in Cornwall, it was serendipitous to discover a parallel reality at Il Vittoriale: that d’Annunzio had also envisaged the building of an open air theatre overlooking the lake. Work began to realise his dream in the early thirties not long after the first plays were performed at Minack.

Designed to recreate a classical amphitheatre, it seats 1500 people and is still in use today. Work started in 1934 and finished in 1952, after the poet’s death.

D’Annunzio lived in his rambling villa which he renovated and developed to his own design with architect Gian Carlo Maroni (1893-1952), writing to him in 1926, ‘I ask you for the architectural framework, but save the decorating for myself… I wish to invent the places in which I live.’ A bit like me in my patch of sky.

On arriving at Il Vittoriale, visitors were shown to one of two waiting rooms. There was one for friends and welcome guests, and there was another for the unwelcome visitors – usually politicians.

The unwelcome visitors would be kept waiting in a small side room. On its wall was a mirror with a cryptic message, which for me has a definite hint of the visitors being put into something of an abyme…

AL VISITATORE.

TECO PORTI LO SPECCHIO

DI NARCISO?

QUESTO È PIOMBATO VETRO,

O MASCHERAIO.

AGGIVSTA LE TUE MASCHERE

AL TUO VISO MA PENSA CHE

SEI VETRO CONTRO ACCIAIO.

To the visitor

What do you bring the mirror

of Narcissus?

This is leaded glass,

or the mask maker.

Adjust your masks

to your face, but be aware that

you’re glass against steel

As Chat GPT describes it, ‘The literary concept of mise en abîme – the technique of placing a story within a story’ seems to me to signify a Janus-like dual reflectivity, and reflexivity come to that, exhibited in d’Annunzio’s complex mentality:

Although d'Annunzio later preached nationalism and never called himself a fascist, he has been credited with partially inventing Italian fascism, as both his ideas and his aesthetics were an influence upon Benito Mussolini. At the same time, he was an influence on Italian socialists and an early inspiration to the first phase of the Italian resistance movement to fascism.2

I’ll explore this doppelgänger, simulacra aspect of mise en abyme in future posts.

Palindromes have a similar quality: Able was I ere I saw Elba.

A Patch of Skyros

I’ve been writing about Rowena Cade appearing in the first and only production of Robert Bridges’ rather dour drama Achilles in Scyros, presented by the Guild, the old girls association at Cheltenham Ladies College in 1912 – the year Alan Turing was born and the Titanic hit an iceberg, by the way. In the gallery of the Castelvecchio in Verona, I then see a picture Achille in Sciro by Nicolo Giolfino (1476-1555) depicting Achilles on the island.

Further reading led me to find out that Philip Gillespie Bainbrigge, the Head of Classics at Shrewsbury School, had written a hilariously risqué parody of Bridge’ Achilles in Scyros in the same year. I then discovered that the father of a fellow student on my MA course at Birkbeck is the archivist of the Shrewsbury School archive and has been able to send me more information about Bainbrigge, a man who was the translator of Proust, Scott Montcrieff’s lover, and who came to know Wilfred Owen before they both died in the trenches.

‘Second Lieutenant Philip Gillespie Bainbrigge, 5th Bn. Lancashire Fusiliers.

Classics Master. Educated at Eton and Trinity, Cambs., he responded to Alington’s invitation to teach at Shrewsbury in order to uphold the great classical tradition, from 1914. Gazetted to the Welsh Regt. in 1917 he later transferred to the Lancashire’s because of family connections. He had taken over from his wounded company commander early in an assault, and was killed in action in France 18 September 1918 aged 27. Buried at Five Points Cemetery, Lechelle, France. Grave B. 24.’

And as if to tidy up the connections, Rupert Brooke, another young poet who died during the First World War, although from illness not wounds, was buried on that same island of Skyros, now spelt with a ‘k’, in 1915.

Canadian poets rule OK.

Given that Rosy’s much loved Canadian aunt died with assistance on Sunday 7th July, I thought it would be appropriate to honour her memory with the work of a couple of Canadian poets.

In the current issue of London Review of Books, there’s a really great poem, a deceptively rough-hewn sonnet, by Canadian poet Karen Solie. I hope she won’t mind me quoting it in full here.

Meadowlark

Prayer in the throat of a non-believer offered up to the absent hereafter, his two long notes and descending warble put him at the centre of things. A partial method, he knows, is no method; but when you are too weak for beauty’s startlement, when you desire not silence but the peace of vague and benign neglect, at decibels audible over the wind, radio, tyres through gravel, through the open driver’s window his song is like arrows of pure math straight into whatever the heart is, its still unbroken land, its native grasses.

Karen Solie teaches creative writing at St Andrews. Her new collection Wellwater is due out in 2025.

Her poem has strong echoes for me with In Flanders Fields3, written by another Canadian poet, surgeon John Mccrae, when contemplating the grave of a dear friend killed in battle at Ypres in 1915. You can read the whole poem on the Poetry Foundation website, but here’s the excerpt Karen Solie’s poem calls to mind.

…in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie, In Flanders fields.

A few quick recommendations, or not.

Apple TV series version of Scott Turow’s Presumed Innocent. Hmmm. ***

Apple TV Lady of the Lake. So far - dreadful *

Two series of Irving Walsh’s Crime on ITV. Fluctuating between * and **** depending on the episode. The humour in the second series seem definitely ‘off’ at times, but then perhaps it’s a bend in the genre.

Very much enjoying listening to an audio book of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts. Brilliant descriptions and what a phenomenal brain behind the writing.

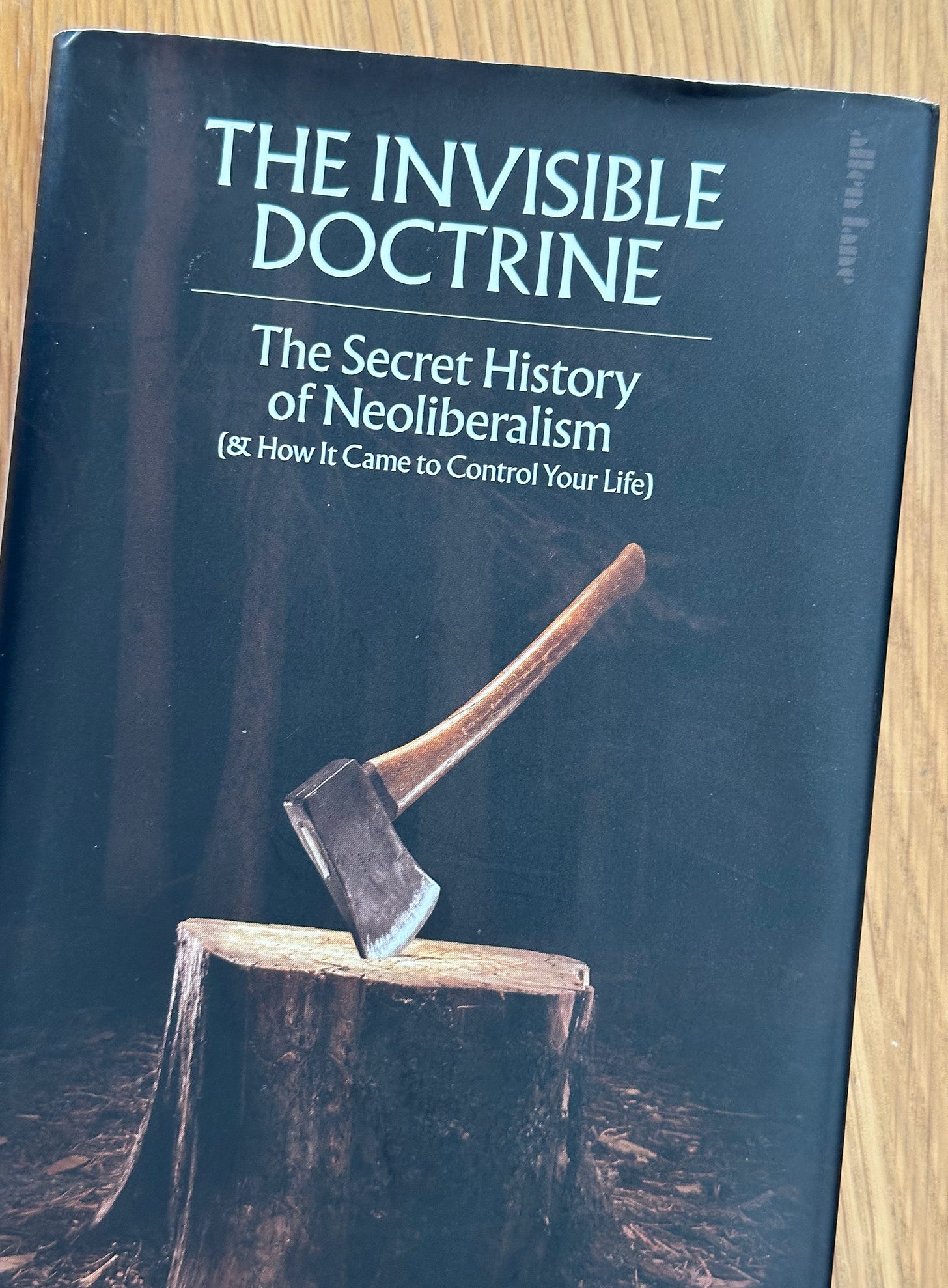

And looking forward to reading a book on loan from Nick White (Central Casting’s latest star), The Invisible Doctrine by George Monbiot and Peter Hutchison. Having served my time as a scriptwriting stormtrooper for neoliberalism, writing propaganda aimed at workforces involved in Thatcherite privatisations or liberalisations, (Jaguar, Leyland Daf, Swan Hunter, Highlands Fabricators, TSB, BUPA, Standard Life) I feel this may get personal! But don’t shoot the pianist.

I could suggest who should be shot but I don’t want to get into the trouble that David Aaronovitch did.

Polishing off the Nazis

On a circular walk around Plumpton we came across The Plough where there’s a memorial to the Polish pilots who flew out of RAF Chailey to fight the Nazis and ensure the continuance of our democracy, however imperfect. I’m sure they are doing loop the loop in their graves at the treachery of the populists across Europe and the USA.

It’s worth remembering that is was the Polish No. 303 Fighter Squadron that was the highest scoring unit during the Battle of Britain, achieving a truly astonishing score of 126 enemy planes, as well as 13 probables and 9 damaged. One of their extraordinary feats was shooting down 14 enemy planes, plus four probables, in one sortie over London on 7 September - the first day of the Blitz - without a single loss on their side. Find out more on the Imperial War Museum website.

I hope the universe is bringing you lots of good connections and sunlight into your patch of sky today, as it is in Brighton.

Till next time here’s a lovely grey gelding called Linc at Hickstead. All 17 hands of him.

'I love deadlines,’ said Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. ‘I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.'

Thanks Wikipedia

I read this poem at Rosy’s father’s funeral. He had kept a hand written copy of the poem. He had been an army medic himself during the Italian campaign in World War II

My home from home in Cambridge in the mid 60s was a pub on Thompsons Lane called the George and Dragon, though it had had other names in its history as a hostelry tucked away near the Cam. The landlord was a Polish pilot who had flown in the Battle of Britain, going solo in just 8 hours. At the time I had joined the University Air Squadron and much to his delight I also went solo in 8 from Marshalls Airfield. One of the pub’s attractions was a proper football table where four of us - Peter Cattermole, Mick Cummins, Alastair Shearer and I - honed our skills. No spinning allowed, though the table was hoist on occasions. Alistair in particular had a fiercesome ability to hold the ball under his goalie’s boots, line up a shot, and then with a powerful flick send the ball flying straight into the mouth of the opposition goal. After reading English literature, he went on to study Sanskrit as a post grad at Lancaster University, publishing a number of works on Buddhism and leading tours to the subcontinent.