Cornwall again

I’d forgotten that I would be in Cornwall again this week, partly for another top-up of Cornish goodness, but also for another opportunity to enrich my experience and observations for the Cornwall centred project I’m working on.

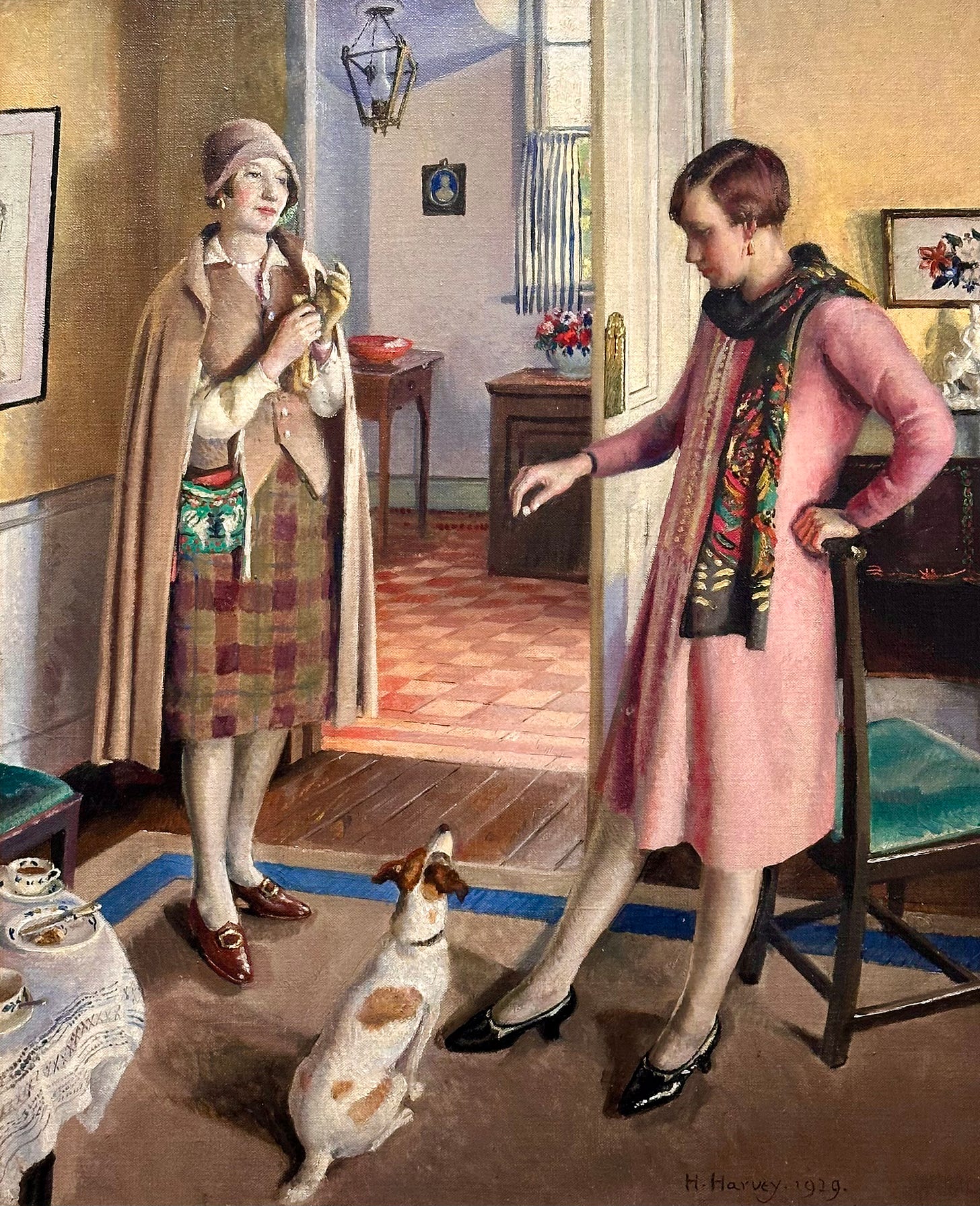

This post was triggered particularly by a visit to Penzance's Penlee House Gallery and Museum, to the exhibition The Exceptional Harold Harvey, a painter I was unaware of until I read the delightful post by Jane Brocket about her own visit to Penzance.

Harvey’s paintings are very useful for me in imagining what life was like in Cornwall before and after the First World War, as I work of my project focussed on that era.

Cornwall by Venn diagram

In that period, Cornwall is productive of lots of different Venn diagrams. The periphery of an area enclosing all the acquaintances of one artist crossing and intersecting with the periphery of an area enclosing those of another, then another, and another, and so on. Newlyn to Lamorna to St Ives to St Buryan. Or the circle of close friends of one group of artists overlapping the circle of close friends of another — and another, of course, and another, and – I just have to say it, don't I? – until the circles are mise en abyme.

Harold Harvey and my subject, Rowena Cade, are on the periphery of each other's circles and knew, or knew of, many of the same people, for example: Laura and Harold Knight, Ernest Procter and his later wife Doris (Dod) Shaw, Samuel John 'Lamorna' Birch, Robert and Eleanor Hughes, Frank and Jessica Heath, and Charles and Ella Naper – with whom Rowena Cade stayed when she first came to Penwith looking for somewhere to live.

Making light of real Cornish work

I very much enjoyed the pictures, full of light, colour and time — Cornish light, colour and time — and most importantly people, portrayed unsentimentally (I felt) but with great fellow feeling and a feeling for work. Here are two young women harvesting iris,

a seaweed gatherer lights his pipe,

a ploughboy calls to his horses,

real quarrymen strain to push a truck,

and young farm workers labour in real earth.

‘Within a year they were probably in the trenches,’ said Rosy seeing this last picture. 'Now everyone is stuck in front of screens,' she added.

I was immediately reminded of hearing someone (who was that?) talking about how important it is to connect with earth, with soil, as Rosy is now doing with a friend as they begin to cultivate an allotment in Brighton that has lain fallow for several years.

I was also reminded of how important it was to me, to lie down on the earth when both my mother and father died, an act of connecting live to earth. I wrote about my 'earthing' after my mother died in the following poem:

Earthed

The day I sheltered there, there was no snow, though snowy hair and winter thoughts had drawn me up past Tilton Wood and Pearson’s Wish. That autumn day I lay down at the foot of Bostal Hill, a miniature of all that lay above, and cried away my grief and all my love. The rhythm of the chalk, its roll and turn, holds me in a strong and timeless trance, the comfort of the ground beneath Bo Peep and Jerry’s Pond. She who once was frozen stone naps now in the hill, the giantess asleep before she wakes to dance.

The role of rock

In a family ravaged by a proneness to bipolar mental illness — one brother held in an asylum, another brother and her younger sister Katharine struggling with it all their lives — Rowena Cade's construction of The Minack Theatre can, I believe, be seen as radical therapy. Her contact with rock and stone, with land and strata, with soil and earth acted as a grounding, a refixing of familial frailty.

Regarding the theatre itself, if you look carefully at the fabric of the theatre, you will see that it’s really a succession of terraces fashioned just like Cornish hedges. The facings have the appropriate angles of the well-constructed Cornish hedge which you see on our farms everywhere, which are still constructed and judged critically by a diminishing number of experts at local ploughing competitions. Of course, Miss Cade acquired these arts from Billy and Charles Thomas and the rest of them over the years, and really got very much of an expert at the job herself…

Charles Thomas was an experienced hedger, and I’ve heard on many occasions Charles Thomas explaining to Miss Cade the technicalities of ‘grounders’ and many other Cornish hedging terms which are still in common use. And there would be Miss Cade and Charles Thomas down there sometimes in a gale of wind and raining…

She dismissed any ideas that she had skills herself and always said, “Well, of course, I picked it up from my friends here.”

…After Miss Cade had been working a few years there with these men, she acquired the same skills and in the end it turned out very often that they would be doing what she suggested and what she did. I mean, she would build a wall just as good as any man.1

The ground of the real

But Rosy has a point. Isn’t connecting to earth positively healthy? Earth is real. Getting your hands dirty in soil is real, isn’t it?

Isn't there a real danger and a danger to the real, that more and more people are not connected to earth, but are more and more sealed in a virtual environment?

Yet, couldn’t they be the pathfinders for a new way of being, a new reality: the Matrix as Mother Nature?

New era

It seems to me there’s the technological possibility of creating virtual experience that feels as real as real, so it will be real. The simulation will be the simulated, increasingly inextricable from it.

In that as yet unachieved context, but in all likelihood to be achieved pretty soon, we will cross over into a completely new state of perception. In fact our virtual experience of being real may prove as refined and qualitatively impressive as the finest audio recording of music or the most beautifully shot film. And if you're worried about missing all the grunge that make the really real real, the virtual real will add back in the background noise you need.

I’m also reminded how many people have told me that in enjoying substances that induce psychedelic experience, they felt they were getting close to Mother Nature; that mind expanding chemicals somehow increased awareness and contact with nature, in whatever way the participant imagined nature to be.

I’d be interested to see a Venn diagram showing the overlap between the group of people who enjoy mind-altering substances with the group of virtual path-finders. Of course it all adds to the constant variegation of life, which will probably end up on three different planes – 1. utterly virtual but real, 2. part virtual/part real, and 3. utterly real, but with lots of overlaps. And mise en abyme, it will probably become increasingly difficult to tell the difference between 1. and 3.

Here it comes again…

Talking of which, I arrived in Cornwall to be greeted by two excellent examples of mise en abyme. Firstly a ‘film-with-in-a-film’ [sic] at The Exchange gallery.

And then at The Exceptional Harold Harvey exhibition, in his painting Laura and Paul Jewill Hill, 1915, there’s a self-portrait of Harold painting away in the mirror, like an Arnolfini tribute act.

My excursion into mise en abyme territory this week has also included reading The Making of Incarnation, Tom McCarthy’s 2021 novel about the production of an epic science fiction film – and a whole lot more. Some have criticised its inundation of technical detail about all manner of disciplines from fluid dynamics to ergonomics, from server farms to astronomy, but I thought this detail proved important in the development of the story. I enjoyed it as a most thought-provoking novel. As the author of Remainder and Satin Island amongst others, Tom McCarthy seems to me to be the high priest of mise en abyme in the modern novel. I’ll write more about this another time!

Real Ale - or not?

Just to bring the happy news that The Yacht Inn in Penzance serves a very well-kept pint of my favourite beer, Bass. It’s a rare find these days. Sadly, although not at all bad, it’s not the brewed in Burton on Trent original that so charmed me for years until it seemed to disappear overnight from pubs across Britain. You can find out why, and just how far Bass is mise en abyme, in this excellent article by Pete Brown.

It’s really very stormy under my patch of sky near Land’s End today (Sunday 29 September), with some spectacular seas. But may your own week be calm and enjoyable. As I mentioned last week, I’m still planning to be off Substack for a while, so see you on the other side. Unless, of course, I’m tempted to post again…

Dick Angove remembers Miss Cade: Interview and extracts from Dick Angove’s Journals (with additional comments by Dick Angove). From Minack Theatre archive, accessed granted 24.4.23

I enjoyed this essay and it is true, to a point, that the virtural, the unreal, the make-believe has crept it and made people believe that what they see, read and feel is real.

But the fun and games of the little boys playing with their tech toys is coming to an end. An inglorious one, to be sure.

I would not call it a sorry end; I would call it a necessary end. We humans are finding out that Mother Nature is no fool, although we have long taken her for one. Make no mistake; the virtural is no match for the real.

With or without substances the natural world in my experience may welcome or reject my presence - or ignore it entirely. I just got back from a week in my home territory, the Golden Valley and environs, from Abergavenny to Hereford, Kington to Ross, and the NW was a bit standoffish, miffed about city life and America, and so on: oh, I suppose American trees are so much bigger, right? And did you miss the drizzle? Here, have some! But on the whole the landscape was glad to see me I to be in it, on it, of it.