Heaven in a wild flower

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Part One.

This is a fairly dense piece extending my exploration of mise en abyme. If you would like something a little lighter today then perhaps explore some of my poems, although some people have suggested they can be a little indigestible too ;-)

Doom Loop (very mise en abyme!)

The beach seal talks to a tourist,

and Edgerley.

Thanks!

Short stories and a serialised novel will be arriving in the new year, so do subscribe now and don’t miss out on future offers.

A world in a grain of sand

Without initially realising it, I think I’m writing a book about mise en abyme, alongside and triggered by my work on Rowena Cade and The Minack Theatre (progressing well, thanks, 220 pages complete and counting.) And if I’m writing a book on this theme, mise en abyme, I may as well have a grand ambition, and that is to show that mise en abyme is more than a clever little literary device but that it is deeply embedded in our human condition, which is why the literary device is so enticing and works so well, of course. It’s part of us. But it is also an ingrained facet and fact of the universe itself.

William Blake’s words come to mind,

To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour.

These are words that can be mise en abyme in cliché, yet can loop back to surprise us with the force of their simplicity. Blake writes about the way the human is embedded in wildness, and the way all other life forms are mise en abyme in human folly.

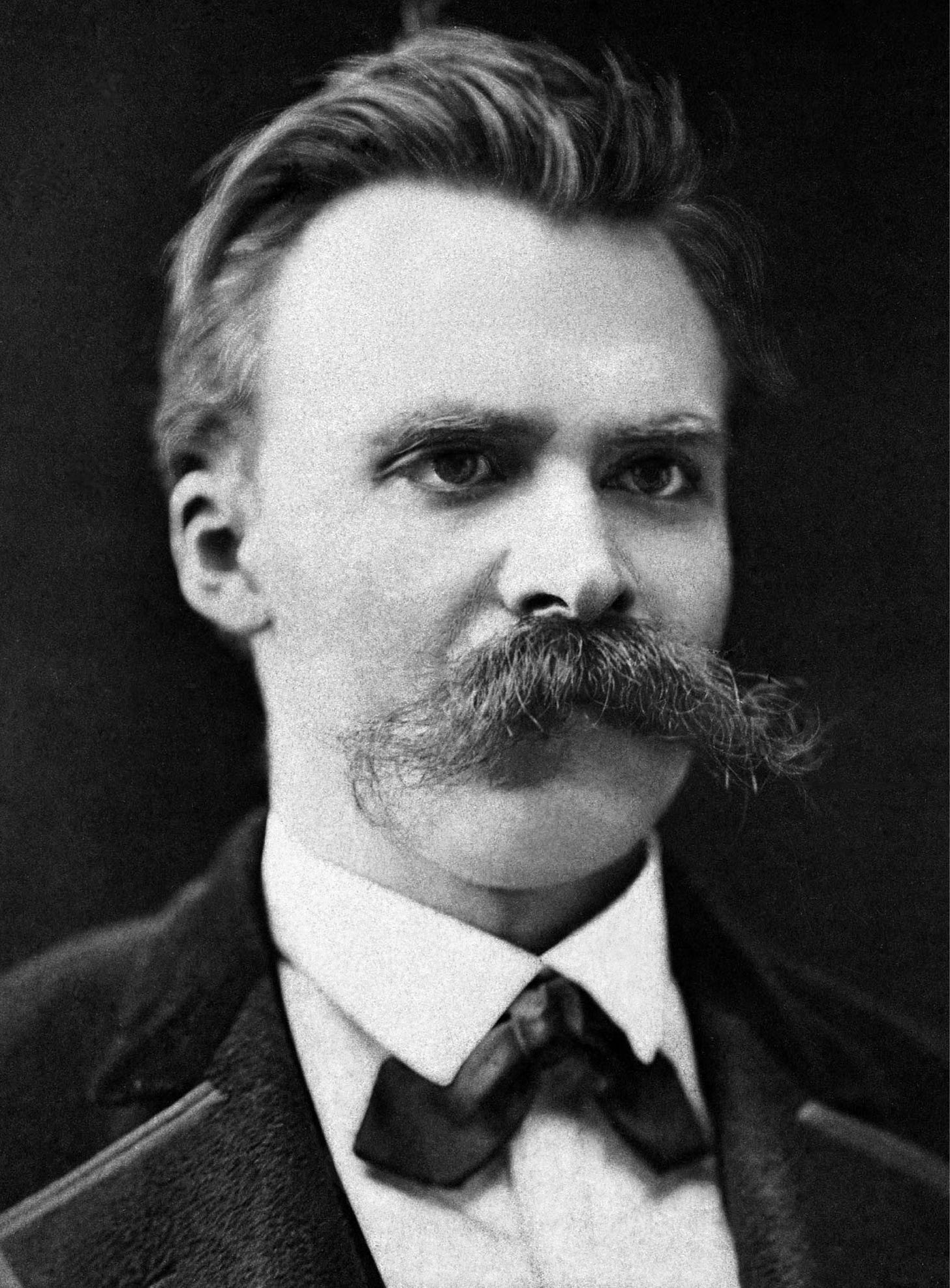

But I’ve a way to go before I get anywhere near achieving my ambition and demonstrating the way the universe and our minds are mise en abyme together. You can get some sense of where I’m heading in Nietzsche’s famous aphorism:

Und wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein.

When you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes back into you.1

I don’t see mise en abyme as good or bad, far from it. To me it’s as neutral as the galaxy, although that comparison may not be as random as it may seem.

We can be mise en abyme when our consciousness is absorbed by some ensorcelling experience like blackberry picking (great harvest this year), playing a computer game or reading a novel. But we can also be mise en abyme through threat or fear, anxiety or dread, or though the enticing bewitchings of populist polticians (please see later).

I guess I’m going off on one, as some might say, so back to business and the job in hand. I’m coming at mise en abyme again, but a little obliquely2. Sometimes that’s the best way to see something. Peripheral vision is the hunter’s gift.

I feel I am constantly shadowed and mirrored by the book about mise en abyme, Lucien Dällenbach’s The Mirror in the Text, which, as I’ll discuss at another time, could just as well be called The Text in the Mirror.

As its author, Lucien Dällenbach points out:

…we know, through a fortuitous note in the Journal, that Gide sometimes wrote in front of a mirror so as to get inspiration from talking and listening to his reflexion:

‘I am writing on the small piece of furniture of Anna Shackleton's that was in my bedroom in the rue de Commailles. That's where I worked; I liked it because I could see myself writing in the double mirror of the desk above the block I was writing on. I looked at myself after each sentence; my reflexion spoke and listened to me, kept me company and sustained my enthusiasm.’3

I’m going to spend a little time re-examining the drift of Dällenbach’s main discussion about mise en abyme, before offering my own views, in Part Two, next time, of a specific manifestation of mise en abyme in politics.

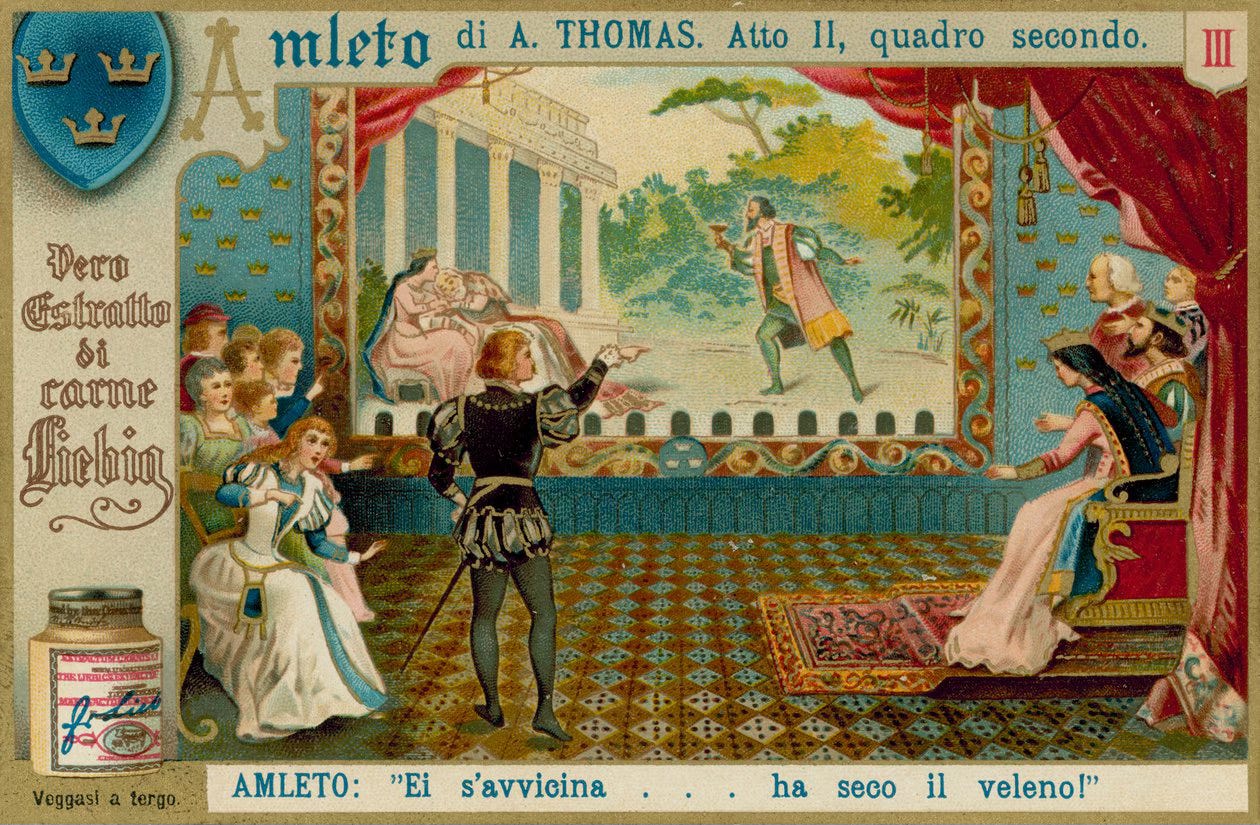

And just to remind you that the inciting incident (as Robert McKee might say) for much of my discussion of mise en abyme, and the centre of its focus, is the play within a play in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Of all the internal duplications in the history of literature, none is more famous than the 'play within the play' in Hamlet. Critics have no difficulty in claiming that it represents the mise en abyme in its purest form, and are not alone in giving it the status of a paradigm.4

Although Gide talked about putting one representation ‘en abyme’ in another, the first person to coin the exact phrase mise en abyme was actually Claude-Edmonde Magny.5

Magny's role as a go-between seems to me to be sufficiently proved by one simple observation: if she had not been the main channel through which the charter became known, the term mise en abyme, which she coined, would not have been accepted so readily by other critics.6

In the next section of his book, The Art of Sidestepping, Dällenbach quotes Magny:

it is easy to imagine intuitively the infinite series of parallel mirrors and the 'internal space' this device introduces into the very heart of the work (interior designers use similar mirror effects to make small rooms look larger) - and also the attraction, the sense of metaphysical vertigo we feel as we peer into this world of reflexions which suddenly opens up beneath our feet; in short, the illusion of mystery and depth inevitably produced by these stories whose structure is thus 'en abyme', in the felicitous phrase of heraldry.7

Dällenbach agrees with the infinite aspect of ‘mise en abyme in this sense’. In a footnote he quotes French poet and ethnographer Michel Leiris, who remembers :

I owe my first actual contact with the notion of infinity to a tin of Dutch cocoa, the raw material of my breakfasts. One side of the tin was decorated with an image of a farm girl in a lace cap, holding in her left hand an identical tin, decorated with the same image of the smiling, pink girl. I still get dizzy imagining this infinite series of an identical image endlessly reproducing the same Dutch girl who, theoretically shrinking without ever disappearing, mockingly stared at me, brandishing her own effigy painted on a cocoa tin identical to the one on which she herself was painted. I suspect that mingled with this first notion of infinity, acquired around the age of ten(?), was a somewhat sinister element: the hallucinatory and actually ineffable character of the Dutch girl, infinitely repeated the way licentious poses can be indefinitely multiplied by means of the reflections in a cleverly manipulated boudoir mirror. (M. Leiris, Manhood, translated by R. Howard (London, Cape, 1968)8

I have memories of being similarly fascinated by such repeated imagery on packaging when a young boy.

Dällenbach considers Magny’s contribution to the study of mise en abyme as if he’s slightly annoyed. In a rather dismissive, mansplaining way, he suggests her approach suffers from a species of disorder and untidiness.

…her commentary, whose capacity for encumbering and obscuring the meaning of the charter is still considerable today... does more than get in the way of the text it is supposed to comment on, it obscures what it sets out to illuminate and it confuses what it should be trying to unravel.9

Dällenbach (referring to Gide’s original description of mise en abyme as ‘the charter’) rather suggests Magny achieves the trick of putting mise en abyme mise en abyme!

He continues:

Everything in the above text - its style, its vocabulary, its imagery - reveals the distortion: the technical term 'abyme' has become a victim of its connotations, has been infected with its metaphysical meaning, and has found itself evoking those images best suited to this metaphysical meaning: mathematical infinity, an 'infinite series of parallel mirrors' , etc.

I can see that I may be guilty of a similar extension and distortion of the term! Dällenbach continues:

And yet these are not the only images that crowd forward under Magny's voluble pen. Unable to control her metaphors, she piles up the most varied comparisons for this single subject: parallel mirrors, mathematical infinity, a feeling of vertigo, a tin whose designs are infinitely repeated, 'the Leibnizian impression of a series of worlds each enclosed within another, in a dizzying series of re-flexions'…10

But eventually, if grudgingly, Dällenbach relents in his criticism of Magny.

A closer examination of Magny's use of it reveals that, … Hidden beneath the critical hotch-potch (an idea of which I have perhaps given), a latent sense of order can be discovered: an unsuspected logic that has lain behind this sliding from one analogy to another.

This logic can be perceived if one tries to classify the paradigms that have emerged to describe the nature of the mise en abyme.

Dällenbach goes on to generalises that:

1 the practice of most critics shows that the mise en abyme and the mirror are sufficiently interchangeable for us to combine the two and to refer to 'the mirror in the text' whenever the device appears; and

2 the term mise en abyme is used unproblematically by authors to group together a collection of distinct things. As in Gide, these can be reduced to three essential figures:

(a) simple duplication (a sequence which is connected by similarity to the work that encloses it;

(b) infinite duplication (a sequence which is connected by similarity to the work that encloses it and which itself includes a sequence that ... etc.); and

(c) aporetic duplication (a sequence that is supposed to enclose the work that encloses it).

The emblematic and unifying use of the mirror by numerous critics is explained by the fact that these three duplications can each, in a way, be related to one or other aspect of mirror reflexion.

Given this threefold division, … it can be said that we stand before these three types of duplication like the three sons in the parable of the three rings; it is impossible to decide which one is the authentic version. Rather than opting arbitrarily for one or another, or restricting ourselves out of loyalty to the charter to internal duplication alone, all three can be accepted as representing the three species of the generic term mise en abyme. This triple recognition challenges any simplistic view and requires a pluralistic definition of the mise en abyme which we might hazard as follows: a 'mise en abyme' is any internal mirror that reflects the whole of the narrative by simple, repeated or 'specious' (or paradoxical) duplication. (My emphasis)

As these drafts of mine on Substack take shape and are tightened up, I hope to show that mise en abyme is as much an aspect of life and living as it is of literature and art. That being in a state of mise en abyme is part of being human, and how we manage that in the era of AI and social media is becoming more and more important. I’ll hazard at my own definition for this:

A mise en abyme is any embedded constituent that acts like a mirror to reflect a whole ( a person, a life, an event, an object) by simple, repeated or 'specious' (or paradoxical) duplication…

Maybe?

I’m away on holiday for a week on the island of Lesbo, so I’ve scheduled this post to publish while I’m away.

We first went to Lesbos in 1988 with all our children and had a great time. I remember being especially struck by the size of the rabbits there who would come out in the evening and graze below the garden wall of the house where we were staying.

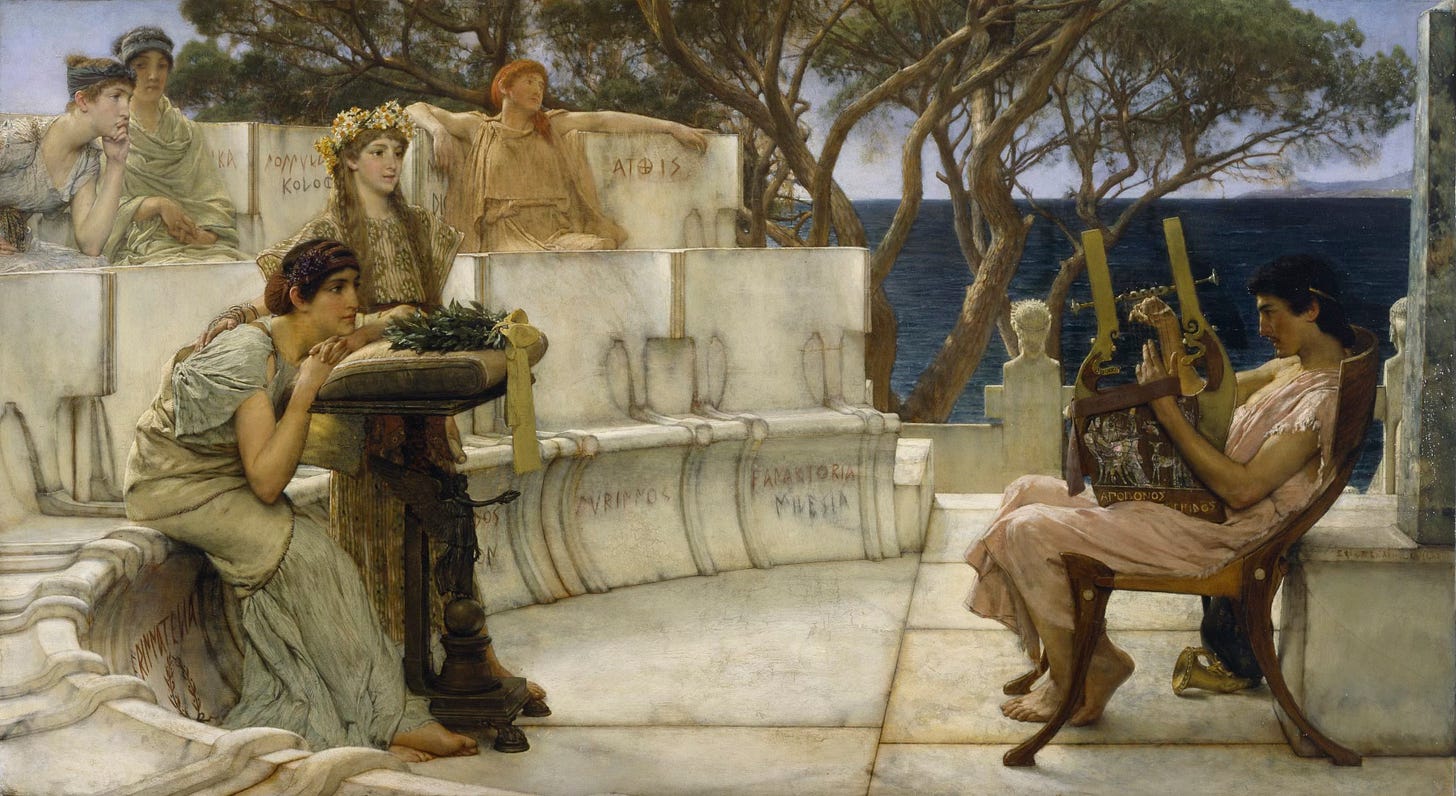

As well as being the home of the poet Sappho, Lesbos is also famous for its connection with Orpheus. Feeling spurned by Orpheus for taking only male lovers (eromenoi), the Ciconian women, followers of Dionysus, first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, but his music was so beautiful even the rocks and branches refused to hit him. Enraged, the women tore him to pieces during the frenzy of their Bacchic orgies.

His head and lyre, still singing mournful songs, floated down the River Hebrus into the sea, after which the winds and waves carried them to the island of Lesbos, at the city of Methymna. There, the inhabitants buried his head and a shrine was built in his honor near Antissa where his oracle prophesied, until it was silenced by Apollo.11

I hope you find happiness under September skies and I look forward to discussing more about mise en abyme in Part Two next time, when I’ll look at other manifestations of mise en abyme according to my extended definition.

Aphorism 146, Beyond Good and Evil, 1886

Strangely I then find a section in Lucien Dällenbach’s The Miirror in the Text which is headed The Art of Sidestepping, which I discuss a little later in the post.

Lucien Dällenbach, The Miirror in the Text (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989), p.16

Ibid, p.12. For previous aspects of my discussion of mise en abyme, see the following earlier posts:

Under the banner of heaven 20.4.24

Let there be light 27.4.24

I’ve looked at clouds 21.5.24

I see no flying horses 30.5.24

Another patch of sky 30.5.24

No patch of sky 16.6.24

A patch of sky above a painted room 11.7.24

Lassù in cielo 21.7.24

Blue sky and hot air 30.7

Under African skies 4.8.24

Claude-Edmonde Magny. Her real name was Edmonde Vinel (1913–1966). In the spring of 1940, she began her collaboration with the magazine Esprit under the pseudonym Claude-Edmonde Magny, alternating reflection articles (about Aldous Huxley in February) and notes on recent literary works. After the war, and until 1951, she gave Esprit a dozen articles on Georges Bataille, the writers of the deportation and Sartre, Joyce, Malraux, Mauriac, Balzac. She was a tutor of French at Newnham College, Cambridge. Dällenbach refers to a chapter entitled The mise enabyme or the cipher of transcendence in Magny’s Histoire du roman Français depuis 1918.

Lucien Dällenbach, The Mirror in the Text (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1989), p.20

Ibid, p.22

Ibid, note 6, p.195. Julien Michel Leiris (1901-1990) was a French surrealist writer and ethnographer. Leiris was also a talented poet, and poetry was important in his approach to the world. In the preface to Haut Mal, suivi de Autres Lancers (Gallimard 1969) he is quoted as saying that “the practice of poetry enables us to posit the Other as an equal” and that poetic inspiration is “a very rare thing, a fleeting gift from Heaven, to which the poet needs to be, at the price of an absolute purity, receptive – and to pay with his unhappiness for the benefits derived from this blessing.” (Discuss, Ed.) In another note (8) p.196, Dällenbach refers to a passage from Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point: 'Put a novelist into the novel. He justifies aesthetic generalizations, which may be interesting - at least to me. He also justifies experiment. Specimens of his work may illustrate other possible or impossible ways of telling a story. And if you have him telling parts of the same story as you are, you can make a variation on the theme. But why draw the line at one novelist inside your novel? Why not a second inside his? And a third inside the novel of the second? And so on to infinity, like those advertisements of Quaker Oats where there's a quaker holding up a box of oats, on which is a picture of another quaker holding another box of oats, on which etc., etc. At about the tenth remove you might have a novelist telling your story in algebraic symbols or in terms of variations in blood pressure, pulse, secretion of ductless glands and reaction times (A. Huxley, Point Counter Point (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1961), pp. 298-9).’ For me, this passage calls to mind the enigmatic personality of Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) and his various heteronyms.

Ibid., p.20

Ibid, p. 22

See https://ancientimes.blogspot.com/2021/06/spurned-women-violent-death-of-orpheus.html written by Mary Hanach. Accessed 3.9.24